The Gist: Packenham Avenue in Chalmette, LA, is named after the British general, Edward M. Packenham, who lost the Battle of New Orleans in 1815.

Yesterday: As Americans, we tend to be very proud yet ignorant of our great history. The War of 1812 is no exception, possibly being the least known American war among contemporary citizens. Basically, the War of 1812 ended up being Britain’s payback for the American Revolution, and this war almost ripped the country apart before any shots were fired. Several Federalists were against the war, whereas President Madison, a Democratic-Republican (if you could ever believe that in today’s political climate), detested the British as did his predecessor Thomas Jefferson. Anti-war New Englanders called it “Mr. Madison’s War” and threatened to secede from the Union that they had just created a few decades earlier. Although the start of the war drew opposing factions, the end of the War of 1812 generated the greatest sense of unity among Americans in their nation’s infancy. And, we have the Battle of New Orleans to thank for it. If you want to be technical, the battle actually took place in Chalmette, Louisiana, just a mile or so outside of the present-day New Orleans city limits.

As long as we are being technical, the British should have had control over New Orleans in the first place, since they defeated the French in the French and Indian War in 1763. The conditions of the Treaty of Paris dictated that all French colonial holdings west of the Mississippi River would be ceded to the Spanish, and everything east of the Mississippi would be subject to the English crown. However, the French and the Spanish devised a scheme to prevent New Orleans (which is technically east of the river) from falling into Britain’s clutches. New Orleans was officially documented as an island, or the “Isle of Orleans,” with all the surrounding bayous and lakes. So, the Spanish would take over New Orleans, not the British. Interesting to note, that the “French Quarter” consists of Spanish architecture as a result of two fires that burned the original French buildings. So, the “French Quarter” may look like the historic districts of Boston or New York if the British had rebuilt it.

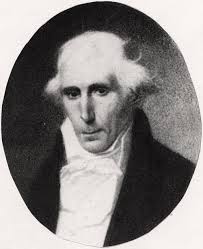

If we still want to be technical about things, the War of 1812 had officially ended on December 24, 1814, when the Treaty of Ghent was signed. However, Sir Edward Packenham did not receive the memo as he was harboring experienced troops on Ship Island off the Mississippi Gulf Coast, preparing to attack New Orleans.

An artist rendition of the Battle of New Orleans painted by war veteran Jean Hyacinthe de Laclotte. Notice Jackson’s strong line of defense. http://www.andrewjackson.org

Many factors were against Packenham. It was foggy when he arrived, and his men were not in proper position, nor was the artillery. The impassable swampland also bogged down his troops, making more time for Jackson to take his position. Most importantly, the British’s plan to turn the Lafitte brothers and their pirates against the United States had backfired. The British offered Pierre and Jean Lafitte prestigious officer positions in the Royal Navy along with large quantities of money if they joined them. Historian Zachariah Frederick Smith wrote in 1904, “[The British] were imprudent enough to disclose to Lafitte the purpose and plans of the great English flotilla in the waters of the Gulf, now ready to enter upon their execution.” Despite having a warrant for their arrest, the Lafittes chose Louisiana over the redcoats and relayed the vital information to Governor Claiborne, who had previously gone to great lengths to capture and try them.

Packenham was an experienced officer (Copenhagen, Martinique, and Nova Scotia) as was most of his troops (Peninsula War, Indies battles, Washington D.C., and Baltimore), but their experience on the battlefield would not save them. Despite having the first tactical advantage of seizing the Villere Plantation house (not the current house at Chalmette Battlefield), they were decimated on January 8th, 1815. General Andrew Jackson led one of the most diverse armies the United States had ever had: whites, free blacks, and Choctaw Indians along with enlisted men, local militia, and pirates. Although the battle included night raids of British encampments and gunboat skirmishes, the day was essentially decided on the battlefield. Andrew Jackson’s forces had built a parapet that provided excellent cover from musket fire, so the redcoats were easy targets as they marched across the field in their redcoats (which would only get redder-if you get my drift). The American casualties (less than 100) were nil in comparison to the British (over 2000).

This painting shows the death of General Packenham as his body was brought to the rear of the English position. An officer weeps with a handkerchief, mourning the tragedy. However, another painting was commissioned to edit that feature in order to make it look more manly and honorable. The revised version shows the English officer pointing across his face. Both versions are on display at The Historic New Orleans Collection galleries.

Packenham went out in a blaze of glory nonetheless. According to The Historic New Orleans Collection, “When General Gibbs rode over to report that his troops refused to follow him, Packenham spurred his horse and dashed to the right side of the lines. Immediately upon taking up the lead of his men, his horse was shot out from under him, and he was wounded in the shoulder. He leaped upon his aid’s horse and galloped a few more yards when he was mortally wounded… The bodies of generals Packenham, Rennie, and Gibbs were disemboweled, placed in casks of rum and returned to the fleet and on to England” (HNOC 103). The British weren’t even informed that the war had officially ended until they had camped on Dauphin Island to pick up the pieces.

Today: It is quite odd that a street is named after a defeated enemy general. I doubt that Gettysburg, PA, has a Robert E. Lee Boulevard or that Yorktown, VA, has a Cornwallis Drive. But, I guess we do things differently down here. St. Bernard Parish actually has several smaller streets named Packenham, some having several spelling variations. Despite my best efforts, I couldn’t find out how this particular street got its name in Chalmette. It runs through Judge Perez Drive and ends at St. Claude/St. Bernard Highway. Chalmette Battlefield and Cemetery is near that intersection. This street is mainly residential with some small businesses.

The Packenham Oaks are located near the battlefield along St. Bernard Highway. It has been rumored that Packenham died from his wounds under the mossy branches. Historians, however, have yet to confirm that claim.

Chalmette, LA, (along with all of St. Bernard Parish) was utterly destroyed by Hurricane Katrina. To give out-of-state readers an idea, this area is adjacent to the Lower 9th Ward in New Orleans and was damaged to the same degree. Residents, however,have rebuilt their communities in “The Parish” on an impressive scale. I never lived in St. Bernard, but I have observed that residents really came together after Katrina to rebuild, and that sense of unity still exists today.

So, sometimes things don’t change, I guess. On January 8, 1815, this area witnessed a unity, resilience, and pride that America needed. Well, “Chalmations” still have those attributes, which New Orleans needs more than ever today.

Tomorrow: Next year marks the bicentennial of the Battle of New Orleans. Chalmette Battlefield is currently planning a special commemoration. I’m sure some impressive reenactments are in store for us. They are also working with race coordinators to organize a run/walk. But, the park is actually taking suggestions from the community. You can go to their website if you want to pitch an idea to them. They are very responsive. I’ve suggested a few things.

Re-enactors commemorating the Battle of New Orleans at Chalmette Battlefield. Credit: NPS.GOV

I always tell people the Battle of New Orleans never ended in 1815, but continues today, especially as we try to make sense of ourselves several years after Katrina. Perhaps we can learn from Jackson’s victory. Tenacity and unity go a long way, yet we don’t need to disembowel English officers to succeed. So, that’s one thing we don’t have to worry about.

Sources:

The Historic New Orleans Collection: History Galleries Notebook. THNOC.

Zachariah Frederick Smith. “The Battle of New Orleans.” http://www.battleofneworleans.us/2013/02/battle-of-new-orleans.html

John Chase. Frenchmen, Desire, and Good Children. 1949

National Park Service. Chalmette Battlefield and Jean Laffite Historical Park and Preserve. http://www.nps.gov/jela/chalmette-battlefield.htm

You must be logged in to post a comment.